The Self Murderers

Here's part of Dante's Inferno associated with Plate 25 of Blake's Illustrations of Dante's Inferno

"Inferno: Canto XIII

"Inferno: Canto XIII

Not yet had Nessus reached the other side,

When we had put ourselves within a wood,

That was not marked by any path whatever.

Not foliage green, but of a dusky colour,

Not branches smooth, but gnarled and intertangled,

Not apple-trees were there, but thorns with poison.

Such tangled thickets have not, nor so dense,

Those savage wild beasts, that in hatred hold

'Twixt Cecina and Corneto the tilled places.

There do the hideous Harpies make their nests,

Who chased the Trojans from the Strophades,

With sad announcement of impending doom;

Broad wings have they, and necks and faces human,

And feet with claws, and their great bellies fledged;

They make laments upon the wondrous trees.

And the good Master: "Ere thou enter farther,

Know that thou art within the second round,"

Thus he began to say, "and shalt be, till

Thou comest out upon the horrible sand;

Therefore look well around, and thou shalt see

Things that will credence give unto my speech."

I heard on all sides lamentations uttered,

And person none beheld I who might make them,

Whence, utterly bewildered, I stood still.

I think he thought that I perhaps might think

So many voices issued through those trunks

From people who concealed themselves from us;

Therefore the Master said: "If thou break off

Some little spray from any of these trees,

The thoughts thou hast will wholly be made vain."

Then stretched I forth my hand a little forward,

And plucked a branchlet off from a great thorn;

And the trunk cried, "Why dost thou mangle me?"

After it had become embrowned with blood,

It recommenced its cry: "Why dost thou rend me?

Hast thou no spirit of pity whatsoever?

Men once we were, and now are changed to trees;

Indeed, thy hand should be more pitiful,

Even if the souls of serpents we had been."

As out of a green brand, that is on fire

At one of the ends, and from the other drips

And hisses with the wind that is escaping;

So from that splinter issued forth together

Both words and blood; whereat I let the tip

Fall, and stood like a man who is afraid.

"Had he been able sooner to believe,"

My Sage made answer, "O thou wounded soul,

What only in my verses he has seen,

Not upon thee had he stretched forth his hand;

Whereas the thing incredible has caused me

To put him to an act which grieveth me.

But tell him who thou wast, so that by way

Of some amends thy fame he may refresh

Up in the world, to which he can return."

And the trunk said: "So thy sweet words allure me,

I cannot silent be; and you be vexed not,

That I a little to discourse am tempted.

I am the one who both keys had in keeping

Of Frederick's heart, and turned them to and fro

So softly in unlocking and in locking,

That from his secrets most men I withheld;

Fidelity I bore the glorious office

So great, I lost thereby my sleep and pulses.

The courtesan who never from the dwelling

Of Caesar turned aside her strumpet eyes,

Death universal and the vice of courts,

Inflamed against me all the other minds,

And they, inflamed, did so inflame Augustus,

That my glad honours turned to dismal mournings.

My spirit, in disdainful exultation,

Thinking by dying to escape disdain,

Made me unjust against myself, the just.

I, by the roots unwonted of this wood,

Do swear to you that never broke I faith

Unto my lord, who was so worthy of honour;

And to the world if one of you return,

Let him my memory comfort, which is lying

Still prostrate from the blow that envy dealt it."

Waited awhile, and then: "Since he is silent,"

The Poet said to me, "lose not the time,

But speak, and question him, if more may please thee."

Whence I to him: "Do thou again inquire

Concerning what thou thinks't will satisfy me;

For I cannot, such pity is in my heart."

Therefore he recommenced: "So may the man

Do for thee freely what thy speech implores,

Spirit incarcerate, again be pleased

To tell us in what way the soul is bound

Within these knots; and tell us, if thou canst,

If any from such members e'er is freed."

Then blew the trunk amain, and afterward

The wind was into such a voice converted:

"With brevity shall be replied to you.

When the exasperated soul abandons

The body whence it rent itself away,

Minos consigns it to the seventh abyss.

It falls into the forest, and no part

Is chosen for it; but where Fortune hurls it,

There like a grain of spelt it germinates.

It springs a sapling, and a forest tree;

The Harpies, feeding then upon its leaves,

Do pain create, and for the pain an outlet.

Like others for our spoils shall we return;

But not that any one may them revest,

For 'tis not just to have what one casts off.

Here we shall drag them, and along the dismal

Forest our bodies shall suspended be,

Each to the thorn of his molested shade."

We were attentive still unto the trunk,

Thinking that more it yet might wish to tell us,

When by a tumult we were overtaken,

In the same way as he is who perceives

The boar and chase approaching to his stand,

Who hears the crashing of the beasts and branches;

And two behold! upon our left-hand side,

Naked and scratched, fleeing so furiously,

That of the forest, every fan they broke.

He who was in advance: "Now help, Death, help!"

And the other one, who seemed to lag too much,

Was shouting: "Lano, were not so alert

Those legs of thine at joustings of the Toppo!"

And then, perchance because his breath was failing,

He grouped himself together with a bush.

Behind them was the forest full of black

She-mastiffs, ravenous, and swift of foot

As greyhounds, who are issuing from the chain.

On him who had crouched down they set their teeth,

And him they lacerated piece by piece,

Thereafter bore away those aching members.

Thereat my Escort took me by the hand,

And led me to the bush, that all in vain

Was weeping from its bloody lacerations.

"O Jacopo," it said, "of Sant' Andrea,

What helped it thee of me to make a screen?

What blame have I in thy nefarious life?"

When near him had the Master stayed his steps,

He said: "Who wast thou, that through wounds so many

Art blowing out with blood thy dolorous speech?"

And he to us: "O souls, that hither come

To look upon the shameful massacre

That has so rent away from me my leaves,

Gather them up beneath the dismal bush;

I of that city was which to the Baptist

Changed its first patron, wherefore he for this

Forever with his art will make it sad.

And were it not that on the pass of Arno

Some glimpses of him are remaining still,

Those citizens, who afterwards rebuilt it

Upon the ashes left by Attila,

In vain had caused their labour to be done.

Of my own house I made myself a gibbet."

For description of the picture go here.

Wikipedia

The Wood of the Self-Murderers: The Harpies and the Suicides

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

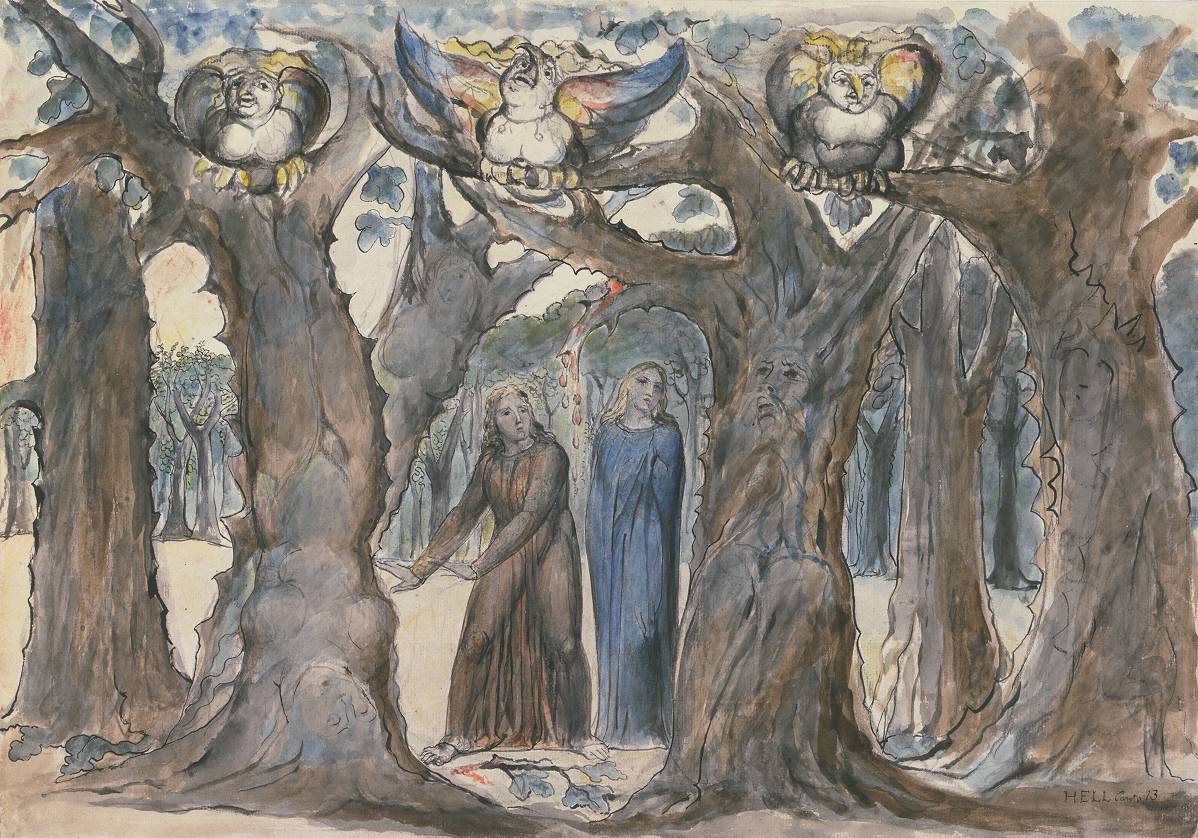

The Wood of the Self-Murderers: The Harpies and the Suicides is a pencil, ink and watercolouron paper artwork by the English poet, painter and printmaker William Blake (1757–1827). The work was completed between 1824 and 1827 and illustrates a passage from the Inferno canticle of theDivine Comedy by Dante Alighieri (1265–1321).[1] The work is part of a series which was to be the last set of watercolours he worked on before his death in August 1827. It is held in the Tate Gallery, London.

Blake was commissioned in 1824 by his friend, the painter John Linnell (1792–1882), to create a series of illustrations based on Dante's poem. Blake was then in his late sixties, yet by legend drafted 100 watercolours on the subject "during a fortnight's illness in bed".[2] Few of them were actually coloured, and only seven gilded.[3] He sets this work in a scene from one of the circles of hell depicted in the Inferno (Circle VII, Ring II, Canto XIII), in which Dante and the Roman poet Virgil (70–19 BCE) travel through a forest haunted by harpies—mythological winged and malign fat-bellied death-spirits who bear features of human heads and female breasts.

The harpies in Dante's version feed from the leaves of oak trees which entomb suicides. At the time Canto XIII (or The Wood of Suicides) was written, suicide was considered by the church as at least equivalent to murder, and a contravention of the Commandment "Thou shalt not kill". Many theologians believed it to be a deeper sin than murder, as it constituted a rejection of God's gift of life.[4] Dante describes a tortured wood infested with harpies, where the act of suicide is punished by encasing the offender in a tree, thus denying eternal life and damning the soul to an eternity as a member of the restless living dead, and prey to the harpies.[5]Blake's painting shows Dante and Virgil walking through a haunted forest at a moment when Dante tears a leaf from a bleeding tree. He drops it in shock on hearing the disembodied words, "Wherefore tear'st me thus? Is there no touch of mercy in thy breast?".[1]

In Dante's poem, the tree contains the body of Pietro della Vigna (1190–1249), an Italian jurist and diplomat, and chancellor and secretary to theEmperor Frederick II (1194–1250). Pietro was a learned man who rose to become a close advisor to the emperor. However, his success was envied by other members of Frederick II's court, and charges that he was wealthier than the emperor and was an agent of the pope were brought against him. Frederick threw Pietro in prison, and had his eyes ripped out. In response, Pietro killed himself by beating his head against the dungeon wall. He is one of four named suicides mentioned in Canto XIII,[6] and represents the notion of a "heroic" suicide.[7]

Describing the scene, Dante wrote:

- Here the repellent harpies make their nests,

- Who drove the Trojans from the Strophades

- With dire announcements of the coming woe.

- They have broad wings, a human neck and face,

- Clawed feet and swollen, feathered bellies; they caw

- Their lamentations in the eerie trees.[5]

Although Pietro does not reveal his identity to the travellers in Dante's episode, he does moralise on the act of suicide, asking (as paraphrased by the historian Wallace Fowlie) if it is better to submit to chastisement and misfortune or take one's own life.[6] In Canto XIII, Pietro says, "I am he that held both keys of Frederick's heart / To lock and to unlock / and well I knew / To turn them with so exquisite an art.[8]

Blake shows a number of contorted human figures embedded in the oak trees in the foreground. To the right, a male figure is seated and wears a crown. A female form is hung upside-down and transformed into a tree on Dante and Virgil's left. This figure may have been inspired by Dante's reference to La Meretrice, or Envy, to whom Pietro attributed his fall.[1] Examining Blake's use of camouflage in the work, the art historian Kathleen Lundeen observes, "The trees appear to be superimposed over the figures as if the two images in the previous illustration has been pulled together into a single focus. Through the art of camouflage, Blake gives us an image in flux, one which is in a perpetual state of transmutation. Now we see trees, now we see people."[9]

Three large harpies perch on branches spanning the pair of travellers, and these creatures are depicted by Blake as monstrous bird–human hybrids, in the words of the art historian Kevin Hutchings, "functioning as iconographic indictments of the act of suicide and its violent negation of the divine human form".[10]

The harpies' faces are human-like except for their pointed beaks, while their bodies are owl-shaped and equipped with claws, sharp wings and female breasts. Blake renders them in a manner faithful to Dante's description in 13:14–16: "Broad are their pennons, of the human form / Their neck and countenance, armed with talons keen / These sit and wail on the dreary mystic wood."[11]

In March 1918, The Wood of the Self-Murderers was sold by Linnell's estate, through Christie's, for £7,665 to the British National Art Collections Fund. The Art Collections Fund presented the painting to the Tate in 1919.[12]

No comments:

Post a Comment