The Harlot and the Giant

From Purgatorio xxxii:

E'en thus the goodly regiment of heav'n

Proceeding, all did pass us, ere the car

Had slop'd his beam. Attendant at the wheels

The damsels turn'd; and on the Gryphon mov'd

The sacred burden, with a pace so smooth,

No feather on him trembled. The fair dame

Who through the wave had drawn me, companied

By Statius and myself, pursued the wheel,

Whose orbit, rolling, mark'd a lesser arch.

Through the high wood, now void (the more her blame,

Who by the serpent was beguil'd) I past

With step in cadence to the harmony

Angelic. Onward had we mov'd, as far

Perchance as arrow at three several flights

Full wing'd had sped, when from her station down

Descended Beatrice. With one voice

All murmur'd "Adam," circling next a plant

Despoil'd of flowers and leaf on every bough.

Its tresses, spreading more as more they rose,

Were such, as 'midst their forest wilds for height

The Indians might have gaz'd at. "Blessed thou!

Gryphon, whose beak hath never pluck'd that tree

Pleasant to taste: for hence the appetite

Was warp'd to evil." Round the stately trunk

Thus shouted forth the rest, to whom return'd

The animal twice-gender'd: "Yea: for so

The generation of the just are sav'd."

And turning to the chariot-pole, to foot

He drew it of the widow'd branch, and bound

There left unto the stock whereon it grew.

As when large floods of radiance from above

Stream, with that radiance mingled, which ascends

Next after setting of the scaly sign,

Our plants then burgeon, and each wears anew

His wonted colours, ere the sun have yok'd

Beneath another star his flamy steeds;

Thus putting forth a hue, more faint than rose,

And deeper than the violet, was renew'd

The plant, erewhile in all its branches bare.

Unearthly was the hymn, which then arose.

I understood it not, nor to the end

Endur'd the harmony. Had I the skill

To pencil forth, how clos'd th' unpitying eyes

Slumb'ring, when Syrinx warbled, (eyes that paid

So dearly for their watching,) then like painter,

That with a model paints, I might design

The manner of my falling into sleep.

But feign who will the slumber cunningly;

I pass it by to when I wak'd, and tell

How suddenly a flash of splendour rent

The curtain of my sleep, and one cries out:

"Arise, what dost thou?" As the chosen three,

On Tabor's mount, admitted to behold

The blossoming of that fair tree, whose fruit

Is coveted of angels, and doth make

Perpetual feast in heaven, to themselves

Returning at the word, whence deeper sleeps

Were broken, that they their tribe diminish'd saw,

Both Moses and Elias gone, and chang'd

The stole their master wore: thus to myself

Returning, over me beheld I stand

The piteous one, who cross the stream had brought

My steps. "And where," all doubting, I exclaim'd,

"Is Beatrice?"--"See her," she replied,

"Beneath the fresh leaf seated on its root.

Behold th' associate choir that circles her.

The others, with a melody more sweet

And more profound, journeying to higher realms,

Upon the Gryphon tend." If there her words

Were clos'd, I know not; but mine eyes had now

Ta'en view of her, by whom all other thoughts

Were barr'd admittance. On the very ground

Alone she sat, as she had there been left

A guard upon the wain, which I beheld

Bound to the twyform beast. The seven nymphs

Did make themselves a cloister round about her,

And in their hands upheld those lights secure

From blast septentrion and the gusty south.

"A little while thou shalt be forester here:

And citizen shalt be forever with me,

Of that true Rome, wherein Christ dwells a Roman

To profit the misguided world, keep now

Thine eyes upon the car; and what thou seest,

Take heed thou write, returning to that place."

Thus Beatrice: at whose feet inclin'd

Devout, at her behest, my thought and eyes,

I, as she bade, directed. Never fire,

With so swift motion, forth a stormy cloud

Leap'd downward from the welkin's farthest bound,

As I beheld the bird of Jove descending

Pounce on the tree, and, as he rush'd, the rind,

Disparting crush beneath him, buds much more

And leaflets. On the car with all his might

He struck, whence, staggering like a ship, it reel'd,

At random driv'n, to starboard now, o'ercome,

And now to larboard, by the vaulting waves.

Next springing up into the chariot's womb

A fox I saw, with hunger seeming pin'd

Of all good food. But, for his ugly sins

The saintly maid rebuking him, away

Scamp'ring he turn'd, fast as his hide-bound corpse

Would bear him. Next, from whence before he came,

I saw the eagle dart into the hull

O' th' car, and leave it with his feathers lin'd;

And then a voice, like that which issues forth

From heart with sorrow riv'd, did issue forth

From heav'n, and, "O poor bark of mine!" it cried,

"How badly art thou freighted!" Then, it seem'd,

That the earth open'd between either wheel,

And I beheld a dragon issue thence,

That through the chariot fix'd his forked train;

And like a wasp that draggeth back the sting,

So drawing forth his baleful train, he dragg'd

Part of the bottom forth, and went his way

Exulting. What remain'd, as lively turf

With green herb, so did clothe itself with plumes,

Which haply had with purpose chaste and kind

Been offer'd; and therewith were cloth'd the wheels,

Both one and other, and the beam, so quickly

A sigh were not breath'd sooner. Thus transform'd,

The holy structure, through its several parts,

Did put forth heads, three on the beam, and one

On every side; the first like oxen horn'd,

But with a single horn upon their front

The four. Like monster sight hath never seen.

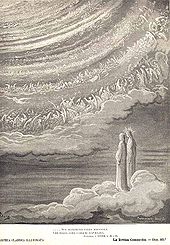

O'er it methought there sat, secure as rock

On mountain's lofty top, a shameless whore,

Whose ken rov'd loosely round her. At her side,

As 't were that none might bear her off, I saw

A giant stand; and ever, and anon

They mingled kisses. But, her lustful eyes

Chancing on me to wander, that fell minion

Scourg'd her from head to foot all o'er; then full

Of jealousy, and fierce with rage, unloos'd

The monster, and dragg'd on, so far across

The forest, that from me its shades alone

Shielded the harlot and the new-form'd brute.

********************************************************

|

| Blake's Illustrations of Dante |

This is the last of the Purgatory series.

Other 'Blake Illustrations'address Paradise.